I’ve missed free-writing and being part of a writing community. So, I joined an online workshop every other Saturday with Donna Jenson of Time to Tell. It’s been so much fun, even when the writing goes deep and into hard cracks and crevices, it doesn’t feel hard, it feels fantastic and wonderful.

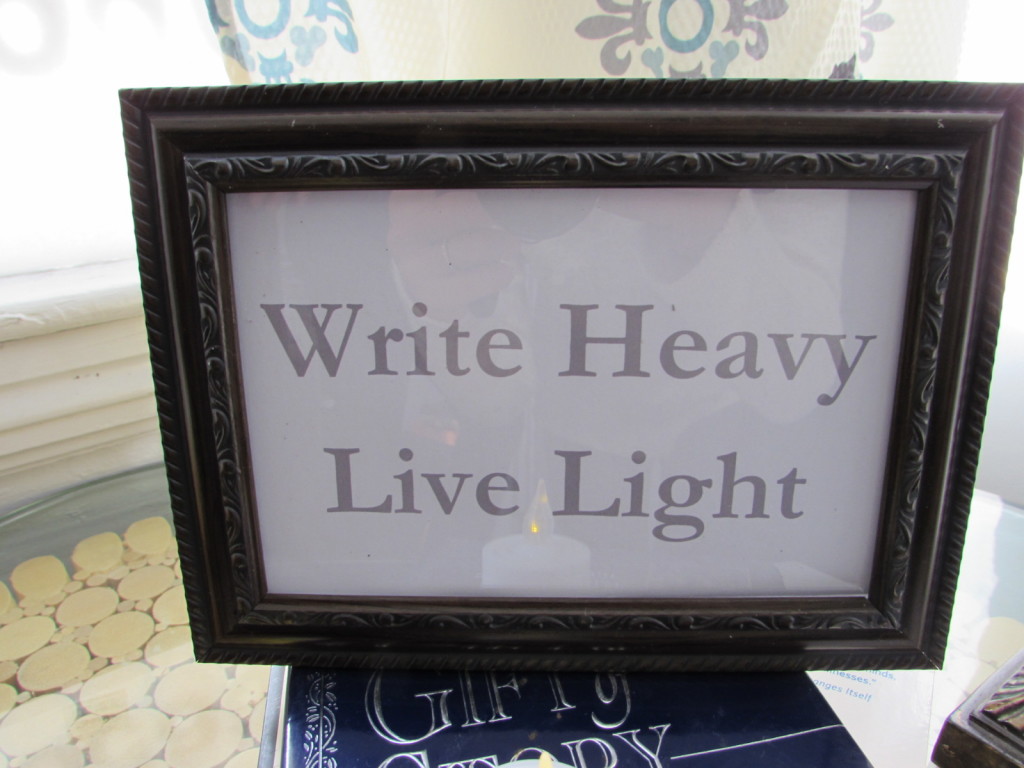

Though I say, often, “Write heavy. Live light,” it still surprises me how often I feel lighter after heavy writing, especially done in community. For me, free-writing works best.

I use stream-of-consciousness writing style, learned from Nancy Slonim Aronie, and I don’t edit, spell-check, or stop moving my hand when I do a first draft. Sometimes, I go back later (especially if sharing the writing on a blog or in an essay, like now), to add punctuation and revisions or quotes. If I’m not posting or publishing or sharing though, I don’t even do that.

This style of writing is about expressing (not impressing), about healing and truth-telling, and connecting with myself and my own writing voice. For me, that’s soul me. If you’ve never tried free-writing, maybe play with the prompt below that was shared with me by Donna and just write about your sacred place.

I’m often surprised as what comes up when I’m prompted, when asked, when we are invited to share.

Writing Prompt 1: “My Sacred Place” (5 minutes)

The unconditional openness of the blankness is always available, always welcoming, never presumptuous. The page doesn’t ask for anything specific.

It’s the opposite of the endless sink piling up over and over with dirty dishes. It’s perpetually possible to start blank, to start fresh, to begin again.

It’s what I love about writing. I imagine it’s what others get by meditating.

It’s not just that I get the chance to meet myself on the page, to dive deep or makye even, as Joan Didion describes, get to know what I think and feel only by writing.

It’s all that but also the place I get to wrestle with ideas, get curious, and ponder on what others say and share. I get to be more open on the page than I am in person.

In real time, I’m often guarded, positioning. In real time, I’m not always free and easy or anxiety enough to be listening well.

On the page, I can be more playful, flexible, and fluid.

On the page I’m not who I was last year, last night, at age 12, or even two decades ago.

The page doesn’t care if I’m a lifelong vegetarian that ate a steak last night for dinner. It doesn’t care if I’m a lifelong Democrat that opted out of voting because I’m not sure either party can steer the boat. The page doesn’t care if it took me twelve times to break up with the same person I knew I loved and couldn’t live with one met after I met him.

The page doesn’t care if my marriage is happy, healthy, or full of compromises which depending on the day may seem good or bad, right or wrong, wise or terrified. Or if I’m divorced or dating or will change marital status 3 more times before I die.

To the page I am as new today as anyone or anything that has ever lived

To the page, I am not fixed and can be contradictory and human and not a hypocrite.

I’ve been in arguments of late, in real life, and I don’t know how to stay engaged without joining a side. I don’t want to battle with anyone, or have to pick a team, as though there’s joy in making others wrong.

Can I open and up share, stay myself, which is sometimes clear and crisp and sometimes unsure?

I remember the early days of college and how “lucky” I was to be the first person in my family to get a BA, and how out of place I felt most of the time with people who were used to having so much so often of most everything.

Today, at 52, I am often the only person in a room. Though I have a house, a car, a good job and am firmly planted in the middle class, I’m often the only one without a long list of letters after my name. A BA, which for me, is a huge accomplishment, is considered so baseline it’s not even worth mentioning, as though of course, that’s presumed not earned or fought for.

And usually, there are no people in the room without a college degree, without a high school diploma, who didn’t get to go through grade school, or who don’t share the same first language.

You seem to fall into the trap of thinking academia isn’t real life, a woman I respect says to me on Twitter.

You seem to fall into the argument that academia isn’t real.

It’s not entirely true. But she’s also not wrong.

I do believe that most people I meet who are academics seem to care most what other academics think, and speak, think, and design studies with only peers in mind – even when, and it seems ironic to me, the area of study is something as equality, equity, or justice. I won’t even get to read their arguments or papers about social justice and their critiques of praise of others because they publish in journals that only other academics can access.

To me, they seem to not know or remember that the vast majority of people on the planet don’t share the same privilege, access, and it’s not because of intelligence or effort but because of the things they seem to be most concerned about, a lack of money, opportunity, child care, and the uneven distribution of resources, finances, opportunity and even emotional and household labor.

I remember the first time I felt my lack of class in college, when the kid asked me to participate in his study and I said yes. He needed to know other three things:

1) My height

2) My Dad’s height

3) My Dad’s occupation

II answered 5 feet 8, not sure, a bum.

The kid laughed.

“No really,” he said.

“Yes, really,” I said or something like that.

I guessed my father was 5 foot 7 or 8 or 9 or 10. I said I think my father was a mechanic in Vietnam but that he’d been homeless most of my life.

The kid look puzzled and I felt red-faced and awkward.

The kid put a note in the margins, like it was a question, like he wasn’t sure if or how to use my data.

People like me didn’t fit into his presumptions, his theory, or his model. People like my father weren’t supposed to be homeless.

How does homelessness impact height?

Did he leave me out? Did he ignore by father because homelessness isn’t a job?

What is done when answers don’t match the limits of questions or the frames or world views of those asking rather than those being asked?

That’s the problem I have with academia. It seems to forget people like me or my Dad. It makes little room for what isn’t presupposed. And then, it’s awkward for those of us who have to point out that there was an oversight that didn’t even account for our existence. And often, we have to do this with people who are supposedly experts on inclusion, human rights, and social justice.

I’m reading Peter Elbow’s book, Everyone Can Write: Essays Toward a Hopeful Theory of Writing and Teaching Writing. His words resonate for me.

“Authors of books and articles in our field have been spending more energy in recent years on arguing why opposing views are wrong, mistaken, misguided-rather than just arguing why their views are right or helpful.”

I see that now as though the battling is sport.

He writes, “as if the only way I can be right is if you are wrong.”

How often this is true about many topics, not just expressive and formal writing.

He says, as one of the obstacles he has faced, himself, as a writer, writing teacher, accused of not being academic enough and accused of doing the very things he doesn’t want to do, which is get into non-refutational argument because “This behavior taps into a pervasive sensitivity to status and the feeling that only one person or team can be dominant; others must be submissive.”

I’ve seen that happening in the ACEs movement, which to me is still new and forming, as though there must be a dominant narrative at all to champion, refute, join, or resist.

The line I underlined, starred, highlighted and copied into my journal and hope to live up to from Elbow’s book is this one:

“The only view I’m fighting against is the view that my view must be eliminated – not the positive content of other views. My goal is to include more points of view and to avoid either/or thinking and zero-sum games.”

It’s hard and important.

I don’t care if we agree or not, share the same views or not. That’s not required. I want to be in conversation, discussion, even debate but not at war.

He writes:

“No one gets to deny or belittle our experience-our sense of what we see and feel. No one gets to interpret or “explain” our experiences unless we invite them to do so and we don’t get to do so for others, either.”

You Matter Mantras

- Trauma sucks. You don't.

- Write to express not to impress.

- It's not trauma informed if it's not informed by trauma survivors.

- Breathing isn't optional.

You Are Invited Too & To:

- Heal Write Now on Facebook

- Parenting with ACEs at the ACEsConectionNetwork

- The #FacesOfPTSD campaign.

- When I'm not post-traumatically pissed or stressed I try to Twitter, Instagram & Pinterest.

Speak Your Mind