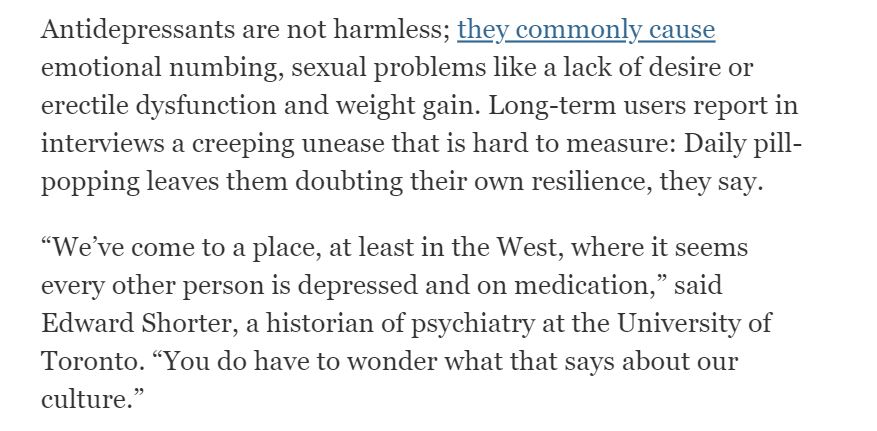

My note: We know antidepressants are widely prescribed. We know there’s a dose-response curve which indicates that as ACE scores go up so do prescriptions for these and anti-anxiety medications. We know a lot less about the process and complications of tapering or stopping these medications, in general, and as relates to those with ACEs.

This New York Times story written by Benedict Carey and Robert Gebeloff and published a few days ago. It already has over 1,000 comments. Here are some excerpts:

and

Here’s the link to the full article.

Cissy’s commentary: I learned of this story this morning when it was shared by the survivor, storyteller, and advocate, Leah Harris, with this comment.

“THIS IS NOT NEWS. Researchers and survivors have known of and spoken loudly about the withdrawal syndrome for decades. We were seen as “fringe,” “discouraging people from seeking treatment,” or “med-shaming” simply for pointing out the harms and risks of antidepressants. Glad these truths are finally getting some cred in the mainstream.”

She’s right.

Survivors and some researchers have been addressing this for years and years and years, in our professional work and in our personal lives – or both. But often, our experiences are treated as symptoms rather than as the crucial feedback.

Listening to survivors isn’t only about making survivors feel seen, heard and believed, as though it’s some act of overdue kindness, some should now be trained to provide. It’s not about soliciting the “lived experience” of survivors but of recognizing all experiences is lived and that’s true for all of us.

It’s about our resilience movement understanding it too needs to be more attuned, regulated and informed – with others and not in isolation. All of our experiences must be considered as valuable, real and raw data.

Too often survivor experiences are relegated only to pathology or symptoms to be discussed or studied by others, as though we are intimately acquainted with our needs, issues, burdens and also our tremendous resourcefulness.

Survivors as central = essential and that means survivors of adverse community and childhood experiences have to be involved, included, represented and with power and influence everywhere. It’s relationships that the trauma-informed movement is obsessed with talking about. But there need to way more relationships with survivors and community members by those making trauma-informed policy or it will just be that – policy.

Discussions about what the community needs should not be had without the community. Decisions that impact the community should be made by those most impacted. Is there a dose-response curve for ACE scorer representation in conversations about ACE-related matters? We need that.

When boards, staffers, and coalitions don’t look, sound, or relate directly to the community itself – what changes? If we all don’t feel the community is us, it’s not ours – not our community. If we all don’t feel trauma-informed policies and procedures speak to and for and about us – all of us – they don’t and won’t.

Here’s one fact I can’t stop thinking about as I’m right here in MA. We know that people of color are disproportionately impacted by ACEs, the pair of ACEs but even just the original ACE study ACEs. And yet, who leads our own non-profits and our efforts towards social justice and change? Are we walking the trauma-informed talk when it comes to our own organizations are organized?

We need leaders who have expertise in all types of ACEs, and who can talk about ACEs as though they impact all of us and not some others? Is it possible that we don’t know this yet? It is.

People are often still making this case as though this is also news. And, to be fair, it is news to some of us but only those of us with privilege. And I’m in my early 50’s and I’m still learning so much about so much. That’s never going to stop. That said, we have to start to at least use what we know, practice what we preach, and help each other get up to speed.

Here are a few good articles for learning more.

- ACE, Place, Race, and Poverty: Building Hope in Children, by Charles Bruner, PhD, MA

- The Race to Lead Series, Building Movement Project

It’s not only unjust or unkind to omit survivors of adverse community and childhood experiences from conversations or issues which impact us most – it’s unwise. To omit first-person experiences shared by millions means continually missing what for many is obvious, already long-known and old news.

Survivors knew, long before research and studies that talk-therapy only approaches were not always helpful. We knew they were even harmful, and re-traumatizing even though evidence-based research didn’t catch or control for that massive miss. How much money could be saved if survivors were just listened to?

Survivors knew, shared, and said how awful some treatments were, privately and collectively. Some were punished or judged for being non-compliant or difficult rather than for being ahead of the times and knowing what researchers would understand only much later on. How much money could have been saved if survivors were valued, heard, and responded to differently instead?

Those with the least power were often punished the most, court-ordered even to treatments that we now know better about. At what cost, human and financial? Even before there was evidence-based proof of harm there was experience-based evidence. It was ignored.

There’s some stuff we can only learn by listening because we don’t all share the same experiences. But what if it was safe for all of us to share our experiences? What if we made more space for those with different experiences to share?

We have not even begun to study or explore what survivors knew, how we’ve coped, managed, thrived despite mind-boggling obstacles. We’ve yet to tap or mine the intelligence of heart and soul that explores how people with historical and generational trauma and disadvantage are so resilient so much of the time. That too is costly and keeps us from operationalizing hope, healing, best practices and practical approaches already known, lived, integrated and used.

And we fail, as well, to deal with the gap in experiences which shapes how we even communicate about ACEs in the first place. To some, knowing 2 in 3 people has at least one ACE is shocking. To some, knowing historical and generational trauma have such a huge impact is news (I put myself in that category). But there are plenty of people who have known both these things and are only surprised that many of us surprised. They, the ones who knew, have known and have been talking about this for all time need to have more voice in the trauma-informed community. That’s the expertise long missing.

We aren’t a singular voice or experience and so token representation isn’t enough. There are those, like me, who have really high ACEs and a boatload of white privilege. My high ACEs in childhood trauma and my low ACEs in community trauma give me a different experience than someone without no or low ACEs in both, or high ACEs in both, or who have high community trauma experiences and no or low childhood trauma. Those are all different and important experiences. Often, we are hearing mostly from those with low ACEs on both counts. They won’t understand, frame, experience the ACEs study or science the same way. We need to translate our experiences and learn from one another. That just doesn’t happen all that much yet in our movement.

Those most impacted have the most insight, the most experience and far too often the least voice, power or representation. If that doesn’t change little else we say, study or research will matter. And this article and issue is just one tiny example of how and why knowing survivors gives important access to what’s already known by survivors.

How much suffering could have been avoided if prescribers, healthcare providers, and others listened to us when we shared about the side effects, risks, complications, as well as t

he benefits, of antidepressant medications – and about a million other topics?

Another piece from the after Oprah ACEs series. Day: A LOT (22) & prior

You Matter Mantras

- Trauma sucks. You don't.

- Write to express not to impress.

- It's not trauma informed if it's not informed by trauma survivors.

- Breathing isn't optional.

You Are Invited Too & To:

- Heal Write Now on Facebook

- Parenting with ACEs at the ACEsConectionNetwork

- The #FacesOfPTSD campaign.

- When I'm not post-traumatically pissed or stressed I try to Twitter, Instagram & Pinterest.

Speak Your Mind