Heidi Aylward spent much of 2015 going to doctor’s appointments for back and joint pain, dizziness, swelling of the legs and feet, high blood pressure, elevated platelets, heart palpitations and extreme fatigue.

2016 isn’t looking much better. She’s worn a heart monitor, had a bone marrow biopsy and continues to have blood work. She holds down a job as a full-time project manager, tends to her daughters, home and pets.

But she feels like her body is falling apart.

“I’m not going to make it to 60,” she said, “Why do I even contribute to my retirement savings account?”

Heidi Aylward: Teenager and Mom.

Heidi is 39.

She’s also one of my best friends.

I can’t help but wonder how much her body is burdened by her chaotic childhood.

For personal and professional reasons, I’ve been learning about the new science of human development, which includes the epidemiology of childhood adversity and how toxic stress from childhood trauma can damage the structure and function of a child’s developing brain. Toxic stress also embeds in a person’s biology to emerge decades later as physical disease.

The CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACE Study) shows that childhood trauma is linked to the adult onset of chronic disease, mental illness, violence and being a victim of violence. The research, led by Dr. Vincent Felitti (Kaiser) and Dr. Robert Anda (CDC) measured 10 types of childhood adversity that occurred before the age of 18.

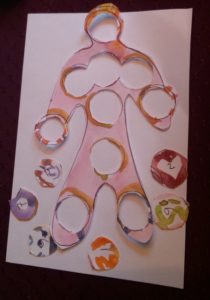

They are physical (1), verbal (2) and sexual abuse (3); physic

ACE Art: Margaret Bellafiore

cal (4) and emotional (5) neglect; a family member who has been incarcerated (6), is abusing alcohol or drugs (7), or has a mental illness (8), witnessing a mother being abused (9); and losing a parent to divorce or separation (10). The lowest possible score is 0 and the highest 10. Of course there are many other types of childhood adversity – bullying, witnessing violence outside the home, being homeless, witnessing a sibling being abuse, experiencing a severe illness or accident – but this study focused just on these 10.

The higher a person’s ACE score, the greater the risk of chronic disease and mental illness. For example, compared with someone who has an ACE score of zero, a person with an ACE score of 4 or more is twice as likely to have heart disease, seven times more likely to be alcoholic and 12 times more likely to attempt suicide. Of the 17,000 mostly white, college-edu cated people with jobs and great health care who participated in the study, 64 percent had an ACE score of 1 or more; 40 percent had 2 or more and 12 percent had an ACE score of 4 or more (i.e., four out of the 10 different types of adversity).

cated people with jobs and great health care who participated in the study, 64 percent had an ACE score of 1 or more; 40 percent had 2 or more and 12 percent had an ACE score of 4 or more (i.e., four out of the 10 different types of adversity).

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) contribute to most of our major chronic health, mental health, economic health and social health issues.

Heidi has an ACE score of 9. I have an 8. This is concerning because those with ACE scores of six or higher die an average of two decades earlier than those with an ACE score of 0. (Got your ACE Score?)

Heidi and I were both diagnosed with PTSD in our 20’s. Combined, we’ve seen our share of therapists, doctors, nurse practitioners, social workers, psychiatrists and healers. We’ve discussed how childhood chaos contributes to lousy moods or relationships, but never poor health, disease, discomfort or premature aging or dying early.

Not one medical professional had talked to either one of us about ACEs or mentioned how early adversity poses health risks and concerns.

In fact, when Heidi asked her doctor about the ACE Study at her appointment, he told her:

“There’s a school of thought that says it’s better not to bring up the past or think about it.” She felt defeated and irked.

“It’s not so much that I was thinking about the past a lot,” she says, “it’s just the way my body reacts to stress.” She thought it might be relevant.

She’s not wrong.

“Hundreds of studies have shown that childhood adversity hurts our mental and physical health, putting us at greater risk for learning disorders, cardiovascular disease, autoimmune disease, depression, obesity, suicide, substance abuse, failed relationships, violence, poor parenting, and early death,” writes Donna Jackson Nakazawa in Childhood Disrupted: How Your Biography Becomes Your Biology and How You Can Heal.

Dr. Jeffrey Brenner, recipient of a 2013 MacArthur Foundation genius award, wrote: “ACE Scores should become a vital sign, as important as height, weight, and blood pressure.”

But they aren’t. Not yet.

“We’re on the cusp of a sea change,” said Jackson Nakazawa, “I don’t think it can happen fast enough.”

She pointed to the nascent ACEs movement, which keeps her optimistic.

There are nearly 10,000 members of ACEsConnection.com, a social network for people who are implementing trauma-informed and resilience-building practices based on ACEs science.

“I think the population is changing ahead of medicine,” she said.

Supporting her optimism for change is the fact that hospitals now have birthing centers and integrative medicine approaches, both of which happened relatively quickly. Neither were “driven by physicians,” she said, but “by patients – and hospital centers realizing they were losing a lot of business” as people left and were willing to travel to birthing clinics or places with integrative approaches.”

As I did.

Motivated entirely by the ACE Study — particularly the statistic about those with an ACE score of 6 who die decades earlier than those with an ACE score of zero — I drove almost an hour out of my way to meet a nurse practitioner in a functional medicine practice.

As a result, I had the single best medical appointment of my life.

See Part Two for a more trauma-informed approach to a high ACE childhood and excellent advice from Lisa Vasile, Nurse Practitioner of Functional Medicine.

You Matter Mantras

- Trauma sucks. You don't.

- Write to express not to impress.

- It's not trauma informed if it's not informed by trauma survivors.

- Breathing isn't optional.

You Are Invited Too & To:

- Heal Write Now on Facebook

- Parenting with ACEs at the ACEsConectionNetwork

- The #FacesOfPTSD campaign.

- When I'm not post-traumatically pissed or stressed I try to Twitter, Instagram & Pinterest.

[…] To read part one of this story, go here: […]