Note: If you don’t like medical pictures you might want to skip this post as there are a few included.

“Hardship is not the problem,” Anne Lamott wrote in Dusk Night Dawn, “it’s the weirdness of it all that wears me down.”

I can agree with that when it comes to life and especially to life with cancer. But I keep wondering what is hardship anyway? What’s hard? What’s easy? It’s so subjective and varies by person and circumstance.

What I do know is I was uncomfortable and unprepared for my PleurX surgery procedure even though it was done at my request.

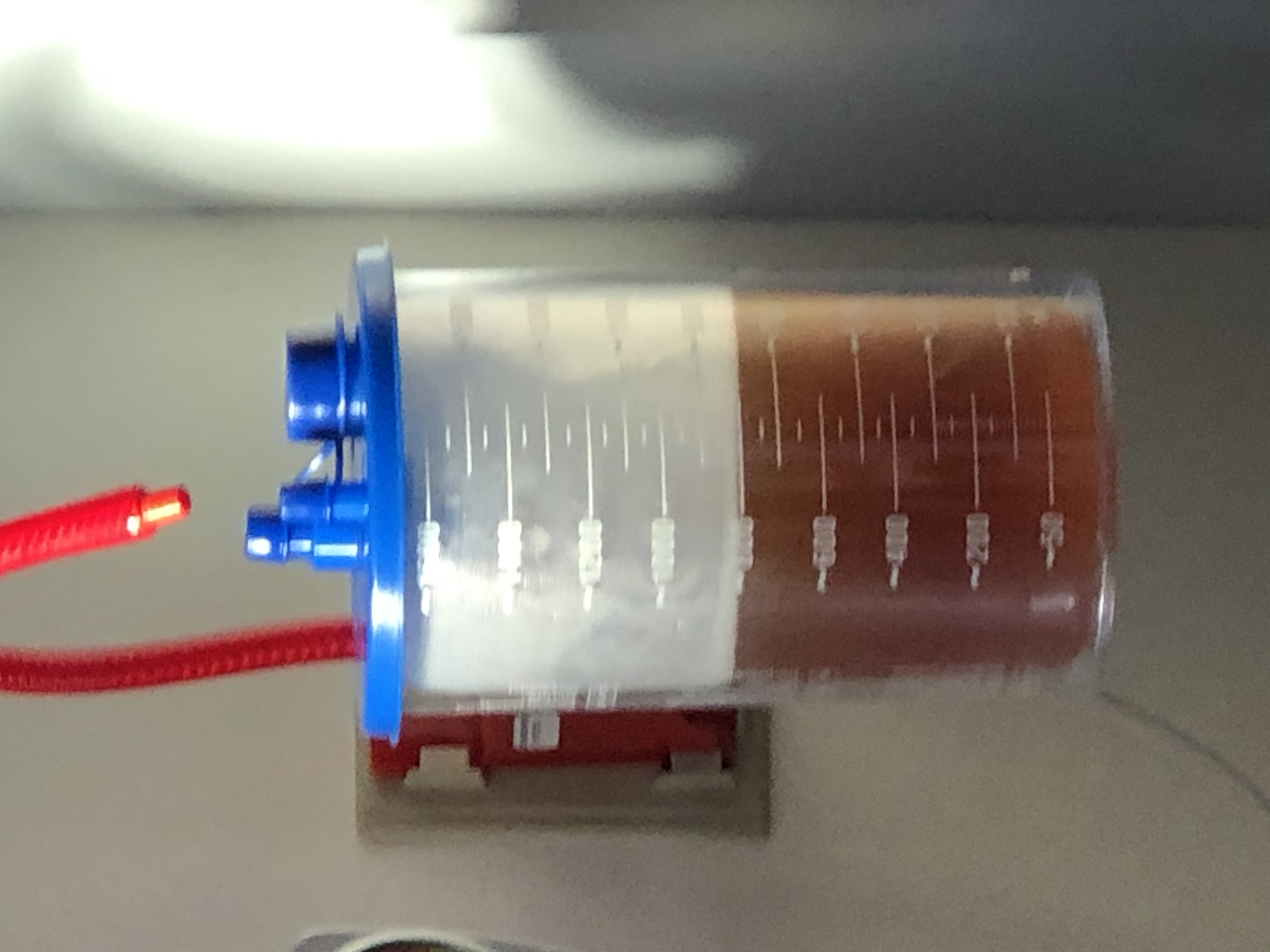

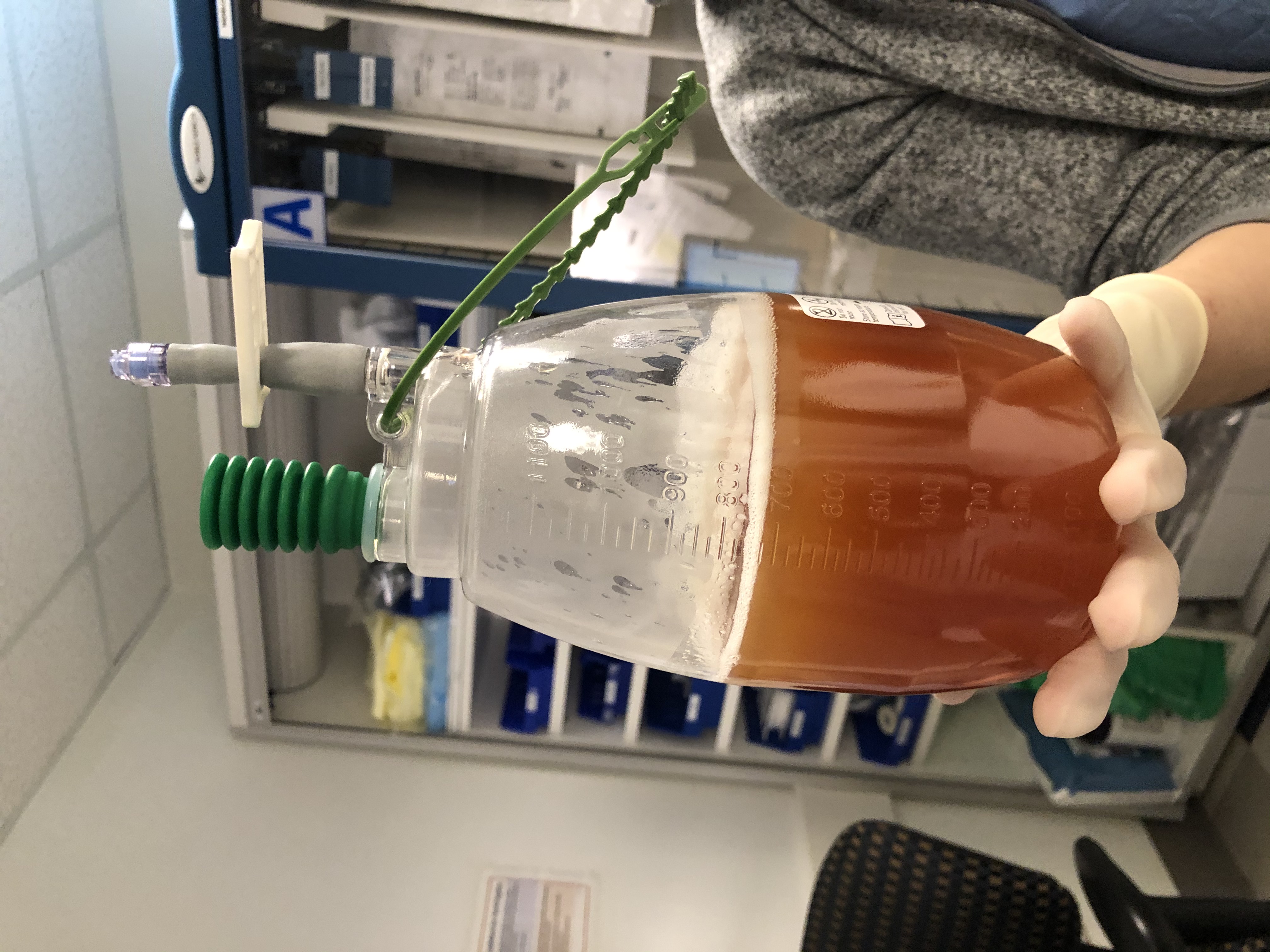

A PleurX is a type of chest tube that can be used at home, allowing me to drain the malignant fluid that accumulates due to #ovariancancer. As the advertisement on the PleurX box boasts, “The difference of living rooms not waiting rooms,” and that pretty much is the whole point of this procedure.

When the fluid collects, it puts me at risk of infection, causes shortness of breath, and jacks my heart rate up to somewhere between 140 to 180. When my heart rate is high, it’s hard to do most anything. I sleep more than half the time and am unable to keep up with my daily walks or stay up past 7p.m., both of which are bad for my physical health, mental health, and for the quality time with my partner, daughter, and pooch.

I’ve had a pleural effusion for months which gets “tapped” by the interventional radiology department in a procedure called a thoracentesis. I want the freedom and agency to drain myself so I can get immediate breath-easier relief without requiring 6 phone calls, 4 emails, 2 car rides, and an hour-long procedure and two-day recovery time, as my partner said, “to tap me like a college keg” and drain what looks like a very large craft beer from my body.

I begged for the procedure and I don’t know why I wasn’t expecting pre-op, post-op, lab drawers, an IV, antibiotics or to feel like a slab of meat on the operating table, but I wasn’t. Nor was I prepared for how painful it would be to have a tube inserted below my skin and above my rib cages, poking into my pleura and stitched into my skin to hold it steady.

It’s mostly my fault because I was not prepared on purpose.

The longer I live with cancer, the less willing I am to give procedures more of my time or energy in advance. Unlike in the past, I didn’t read 20 articles in advance, didn’t ask 10 others survivors if they had the same procedure, or how to prepare and recover, and I didn’t even drill the doctor with tons and tons of questions.

The doctor doing the surgery was a fellow, a fancy word for new at his job, and he appeared while I was sitting to give me an overview of the procedure with an attending standing right next to him to supervise.

I kept saying, to anyone and everyone, “no sedation – only – local,” because I was afraid someone would accidentally knock me out. The doctor asked why I didn’t want sedation and I wanted to say, “Because I don’t want it” in a “my body and my choice” tone of voice. But I didn’t.

“I don’t like to be out of it. I like to have my wits about me,” I said. I left out the other part, how I was molested while I was sleeping and I don’t like to be naked, helpless, and unconscious around others – especially strangers.

How often do we protect medical providers from uncomfortable topics because we know that our answers aren’t on the list of what they’re expecting when they ask a question? I kept my past to myself even though I know I’m not the only one who feels extra protective of my unconscious body. Unfortunately, many patients have a history of childhood sexual abuse and/or trauma happening in adulthood (or both).

I’d asked if I could have local sedation for my hysterectomy and my surgeon gave me a hard now. However, she asked why I requested it to see if I could get my needs met another way. With her, I was honest and told her about my history of trauma and sexual abuse. She told me me that a gynecologist oncologist sees her fair share of survivors and that we tend to fall into two distinct groups:

Those who want to be knocked out and drugged as hard and long as is possible and those who want few to no drugs and to be as aware and awake as possible.

I usually just joke with medical people that I’m a ‘control freak,” but I don’t usually share what made me one even though it might impact interactions.

2 of the nurses whispered to me that they wouldn’t do sedation for a PleurX surgery but made sure to ask me not to share that with the doctors and to be clear the no sedation request came from me – not them. I wonder if this is because the doctors prefer patients passed out, compliant, and unable to move or ask too many questions?

The operating room was high-tech. There were at least six oversized computer monitors as well as several ultrasound machines. I was placed on a thin and metal table where I was strapped in so I wouldn’t fall off. Foam wedges were put under my hip and my back so I’d be propped up in a semi twist position to make my ribs accessible to the doctors.

Hanging over me was an ultrasound machine so the fellow could see where the needle was inside my body, and where the four inches of tubing should go to get between my rib bones into the pleural space. The procedure took about an hour and I had to wear the pulse oxygen meter on my finger and a blood pressure cuff during the entire procedure. The OR nurse appeared four or five times to ask me how I was doing and to answer questions since I couldn’t see what was happening.

The doctors were only inches away from my head but since I was on my side I couldn’t see them. Why they didn’t do the procedure on the other side of me so I could see them the whole time is beyond me. It would have made the surgery much less frightening. I asked them to tell me what they were doing but that didn’t happen much.

I was numb from the lidocaine shots and didn’t have any pain or even know when the first cut was made. I did feel the pressure of the fellow’s fingers and tubes moving inside of me, threading the tubing under my skin the way I have done when the drawstring in my pj’s break and need to be painstakingly reinserted.

It’s hard to be in the hospital without loved ones to help pass the time. I hate being a patient, wearing a johnny, and carrying all of my belongings in a plastic bag. I hate being shuffled around from room to room to room.

A nurse case manager got me from the waiting room and took me to a chair in the back to ask me questions and prepare me for the recovery. She was friendly and kind.

“We want to send out a visiting nurse,” she said, to help with wound management and to learn how to use the drain.

“O.k.,” I said, but it didn’t feel o.k. “I don’t need that,” I wanted to say, except I wasn’t sure it would be true post-op.

She peppered me with questions and took notes.

“How many stairs do you have to walk to get into your house?”

“Are there handles in the shower?”

“Can people in your home help you with your basic needs?”

“Do you have a ride home today?”

“Do you have crutches or a wheelchair?”

I started to get angry and defensive. I wanted to scream SLOW DOWN. I said, “I have help but I don’t need it that much. I have stairs and I can manage them just fine. Bathing and showering? Not an issue for me.”

She wasn’t being rude or invasive. She wanted to make sure I had enough assistance and support.

She was there to help me. But I didn’t want to be a person who needed help.

I wasn’t mad at her – I was furious at cancer, angry at being disabled, and exhausted from procedures that are all palliative because managing my disease, rather than eradicating or curing it, is the best modern medicine has to offer me.

Angry inside is my default response. I don’t always express it, and can often suppress it behind politeness, but often I’m managing some irritation.

When the doctors say I look too healthy to be sick, I get mad, because I am.

When they say I’m too young to have cancer, I get mad because I have cancer.

When they offer more support than I’m ready for, I get scared.

When they fail to provide information or answer questions, I get confused.

When they challenge or dismiss my concerns, I feel small.

Mostly, I want to say one of two things:

1)Consider me a partner and collaborator in my care when it comes to my disease and any procedures being done to me (like I’m the customer at the Apple store and the service is at least somewhat important as the product if not more so).

2)Tread lightly when commenting about my personal life, needs, or appearance because often it’s always unnecessary, especially if we don’t have a good rapport, and it’s sometimes insensitive or offensive.

One nurse asked if there is any chance I could be pregnant and I laughed out loud. “I have ovarian cancer,” I said. “I don’t have many organs left above my thighs. Inside, I’ve been scraped hollow like a carved-out pumpkin.”

“It takes a lot to make me blush,” one nurse said, “but that did it,” and then he stopped putting in my IV because he was laughing so hard.

“It would be some miracle for me to pregnant,” I said, “Unless the hospital accidentally forgot to take out my fallopian tubes, ovaries, cervix, and uterus, etc.” Plus, I’m menopausal, on chemo, and am here for a pleural effusion because I can’t breathe and also have a pericardial effusion so I can’t exercise – so it’s safe to say sex isn’t a real high priority right now either.”

“There’s no chance I could be pregnant,” I said. I didn’t say, “Obviously no one read my frickin file, huh?”

But I get it, I’m one in a long line of patients the nurses see every day so I try to act agreeable even when I’m irked because the people I meet are at work and just doing a job and have many others to attend to besides me.

“We’re giving you an IV antibiotic,” the operating nurse said.

“Why?” I asked.

“To prevent an infection,” she said.

“Is that optional?” Can I get antibiotics only if I get an infection?” I asked.

“I’ll ask the doctor,” she said, “But can you tell me why?”

I explained that chemo is less effective after antibiotics are given and can impact my overall survival.

The attending came over to talk to the back of my head and said, “You need antibiotics. You’ll be in real trouble if you get an infection.”

“I’ve got advanced ovarian cancer,” I said, “so I’m way past real trouble already.”

I explained for me, this procedure is to reduce pain but chemo is to fight cancer. Cancer is my big problem and this, in comparison, is a small one.

“We give antibiotics for this procedure,” he said.

“Are you saying I have to get off this table and not have this procedure if I refuse antibiotics or are you saying you would like it if I followed your protocol and took antibiotics?”

“Look,” the attending said, not hiding he was annoyed, “You are not on a 10-day dose of antibiotics. You are getting one dose. The antibiotics will clear your system before chemo.”

I relented because I didn’t have the energy to keep arguing and didn’t feel like pulling up Google scholar to research IV antibiotics and chemo while half-naked and in a pretzel twist position. And, I couldn’t image walking off the table mostly naked and messing up the schedule of an entire team.

This is why I don’t like to be asleep, If I was asleep, I wouldn’t even know they were giving antibiotics. If I were asleep, I couldn’t inquire, assess, or even change plans. This is why I like people to be with me. It’s hard to self-advocate in a room of six or more people, multiple computer monitors, and oversized machinery displaying my insides to the medical team while I stare at the wall squeezing the metal edge of the bed hard, counting 1 Mississippi, 2 Mississippi, and waiting for it to end.

When it was over, the nurses un taped the privacy paper, took off the heart monitor electrodes, and blood pressure cuff, and put me in a wheelchair riding me back tot he post-op area where I could put my clothes back on.

There, I was given a short tutorial and a YouTube link on how to use the PleurX drainage kit while I waited for a chest x-ray to make sure the procedure went smoothly.

However, once I was five minutes from home, still in the car, the surgeon called me to ask me to come back to the hospital.

“You have air in your lung,” he said.

“Isn’t that a good thing?” I asked.

“We got air in your lung from the procedure,” he said, that thing he had warned me about but said never happens had indeed happened.

“Didn’t anyone look at my x-ray before I left?” I asked, confused.

“I can only tell you I’m calling you now and I just saw it.”

“That’s not a good answer,” I said, “What’s the mechanism or a procedure in place so that this doesn’t happen to me in the future or to anyone else?”

Crickets.

“Are you going to come back to the hospital now?” he asked.

“I’m not sure,” I said. “What are the signs of if there’s a problem? What are the chances, statistically speaking, that this will cause a problem?”

I told him my partner already took time off to pick me up, and getting in and out of Boston is time-consuming, especially when our loved ones can’t wait in the hospital with us due to COVID.

He agreed to check up on me twice, later in the day, told me to go to the ER if there was any pain or shortness of breath, and then he said, “If you go to the ER, tell them you have a PleurX because they can remove air that way.”

I asked, “Can I use my PleurX today or tomorrow to remove air?”

He said, “It can’t hurt and it might help.”

So that is what I did after watching some YouTube videos because the longer I am sick with cancer, the less willing I am to spend time in any hospital. My reason for getting a Pleurex was to be able to manage my symptoms better from home.

While this was the goal, the reality is that after my “starter kit” of four Pleurx bottles ran out no one was able to help me find or order replacements (I needed 12 to 24). The hospital told me to call the visiting nurses, the visiting nurses told me to call insurance, insurance sent me a list of medical distributors, the medical distributors didn’t carry the item, except for two of them, and those two didn’t take my insurance. The out of pocket cost for the bottles was $1,000 and since I’m now on full-time disability I can’t pay for that.

If I couldn’t find them I would have needed to reverse the surgery, return to outpatient taps, or go to interventional radiology at the hospital to be tapped every other day. This would have been helpful information to know before surgery.

I share this not to complain endlessly but because even in the state of MA, where this professional advocate lives and works, has access to healthcare, and has a past history of being a reporter comfortable enough with awkward or direct questions, I’ve still been delayed, frustrated, and had my life made more complicated not only because of cancer, and cancer treatment but because of medical and insurance system who don’t always communicate or know the context of a patient’s condition(s) or life.

It was not fun the day after chemo, when I generally wake at 4a.m. on a steroid high to have to make multiple calls to the oncology team, to the department that did my PleurX surgery, or to make six calls to medical supply companies. This doesn’t even including the emails and texts sent back and forth or the re-scheduled appointments with the visiting nurses who can’t help me clean, drain, and dress my wound without the PleurX kit supplies.

My friend Beth, a retired social worker, asked what do people do who are sicker, more disabled, tired, worn out, who also have to work, who are raising kids, who don’t have insurance or who speak another language or who don’t have the energy to advocate for and fight for themselves?

That is the question that many ask but don’t actually address. It’s part of why patients don’t have equal access to care. And if I’m getting among the best treatment that exists in the world, as a patient advocate, and this is my experience, I can’t imagine what other people go through? Medical stuff is tiring and frustrating to everyone but when you have been told you have two to three years to live, and are making sure to use time wisely, it can be infuriating to spend hours and hours to get treatment. This ends up being one of the biggest and most consistently stressful time sucks but for too many of us it is.

I wondered if I was particularly unlucky but as I read more blogs by writers with metastatic cancer, I’m learning that this is the norm. See Abigail’s post on Dignity and Nadia’s Tweets on requesting her care, advocating for her rights, and visits while in the hospital. We learn to advocate for ourselves and get better at it. But should we have to work this hard while we are being cared for, are sick, and sometimes can’t insist we get better care.

Even if our cancer can’t be cured or even well-treated, I wish there were more care and compassion for those of us with cancer so that we can better cherish the time and life we have. Luckily, not all of my experiences have been challenging.

When I went to check if I had fluid in my stomach (called ascites), and had my lung fluid checked, the team looked at how angry my wound was becoming and suggested removing it. They also wanted to give me antibiotics. First, they checked in with my oncologist and when he called back he asked to be put on speaker phone and spoke directly to me. He asked me what I thought, what I wanted and when I shared my concern about antibiotics he said we could hold off as long as I monitored the injury, sent pictures to the patient portal of how it was healing, watched out for fever, etc. I felt cared for and cared about and understood why I might need antibiotics but that it was possible with where my white counts were at, I might not. I’m not sure my oncologist ever got any training in being trauma-informed. But by being collaborative, curious, communicative, and kind, that’s what he is.

Note: After two rounds of low-dose Carbo/Doxil chemotherapy the fluid around my heart is gone and the fluid in my right lung significantly reduced. I can breathe easier. I can now do exercise and cardio.

I seem to have avoided infection after the chest tube was removed. But wow, that process was super painful and the healing from it was lengthier and harder than expected.

It may be because I’m on a type of chemo (Doxil) that impacts the skin and wound healing so that, along with having lower red and white counts. Whatever it is, the healing has finally happened (and is much better than it looks above). I don’t need to avoid baths or swimming. I don’t need to apply ointment or bandages. YES! YES! YES!

Today, I return to chemo (round 3) and hope my CA125 (tumor marker) is coming down. Fingers, toes, and everything else crossed!!

You Matter Mantras

- Trauma sucks. You don't.

- Write to express not to impress.

- It's not trauma informed if it's not informed by trauma survivors.

- Breathing isn't optional.

You Are Invited Too & To:

- Heal Write Now on Facebook

- Parenting with ACEs at the ACEsConectionNetwork

- The #FacesOfPTSD campaign.

- When I'm not post-traumatically pissed or stressed I try to Twitter, Instagram & Pinterest.

This self-advocacy thing is HARD and reliving trauma over and over is so triggering. I’m so sorry that you’ve had these experiences too. I wholeheartedly agree that the people in the medical system just want us to lay back, comply, and make their jobs easier. When we need something different because we’re all unique individuals and have unique needs, it makes them stop and think. And yet, my hope always is that by making them think in this moment, maybe they will think more with the next patient. One can only hope!! Sending love and hugs. ❤️

Abigail:

Thank you for this comment. I try to be vocal in a way that isn’t raging so I don’t get dismissed. It’s not easy and it’s especially hard when alone, not dressed, in pain, etc.

But I also think it’s important to help providers understand our experiences at the hospital, during visits, and also at home. And I like and learn when providers share with me and we can have a conversation. That is also powerful. Today, I was talking to the oncology nurse about how the “Hazardous Drug” bags are a little disconcerting to see when they are the drug that gets injected and is supposed to help and when it goes directly in our arms and the nurses are gowned, gloved, and double-masked. The nurse told me, if there’s an allergic reaction, it’s good to have a big, yellow, clearly marked bag to be clear on what the drug is, fast, without looking in the computer. And while I still think there are patient sensitive ways to accomplish this, it helped me better understand the practice and the goals of it and why it’s done. I love that. The conversations help. The info. helps. We also need context but we don’t get it when treated as cookies or products on a conveyor belt and that’s why ruffles my feathers, triggers me, or sometimes offends. I LOVE your blog and your posts and your advocacy.

In it together, as my friend Donna says, in it together!!!

Cis